Are You Prepared for the Consequences?

Suppliers of flow meters and other hydraulic components generally stipulate their products be used only by qualified personnel. This protects them from liability if an incident occurs due to lack of proper training or negligence, especially from not reading instructions on proper and safe use. In my 30+ years involvement with hydraulics technology, I’ve heard time and again that most hydraulic maintenance technicians acquire much of skills through trial-and-error techniques, rather than from professional training. So many in the workforce may be an accident waiting to happen. Are you one?

Even though a hydraulic flow meter is a pretty straightforward instrument, potential users should first be trained in the basic principles of hydraulics, how to test hydraulic systems, circuits, and components, and hydraulic safety. Hydraulic systems present a wide array of potential safety hazards, so an awareness of these safety hazards can only be garnered through training that focuses on all aspects of hydraulic safety.

Case In Point

Rory McLaren, Director of the Fluid Power Safety Institute, in Salt Lake City, shared a specific example illustrating these conditions with me.

Having no formal training in hydraulics or hydraulic safety, a mechanic was instructed by his supervisor to determine why the bucket on the company’s front-end loader drifted downward. He was told worn piston seals could cause this problem by letting fluid leak internally from the high-pressure side of the piston to the low-pressure side, so the mechanic decided to use a flow meter to determine the leakage.

Although he had never used a flow meter before, the mechanic had seen one used for testing a pump. He found an inline flow meter lying on a shelf, so he cleaned it up and installed the adaptors needed to connect the flow meter to the cylinder. The most-accessible hydraulic line was at the rod end of the cylinder, so he proceeded.

He had no idea that the flow meter he selected was designed to permit flow in only one direction. It was not obvious that it was intended for one-way flow; the only indication was from the model number. Rory notes that manufacturers of in-line flow meters should — but often do not — clearly indicate on the flow meter itself whether a it is unidirectional or bidirectional.

Once the mechanic had installed the flow meter, he asked an operator to start the machine and cycle the cylinder back and forth as he observed the flow meter. Within seconds, a thunderous explosion occurred as the flow meter burst. Oil discharged from a gaping hole at extreme velocity and pummeled the mechanic’s body. The geyser of oil knocked off his hardhat and safety glasses and struck him in the face. The operator immediately down shut the machine and rushed to the mechanic’s aid. The mechanic was fortunate that he did not suffer a serious injury.

The supervisor, who was as ignorant about hydraulics as the mechanic, wrote off the failure as a “defective flow meter.” An investigation to determine the root cause of the failure was never conducted. A near-miss report wasn’t even written about the incident. This negligence almost guarantees the same mistake will likely be repeated, and with the potential of more dire consequences.

A Better Scenario

Training certainly could have prevented this accident. A course in basic hydraulics would have taught the mechanic about force, pressure, and area as it applies to hydraulic cylinders. He would have learned that a double-acting, single rod hydraulic cylinder can intensify pressure and flow. He also would have learned that components designed for one-way flow — such as the flow meter —often contain a check valve.

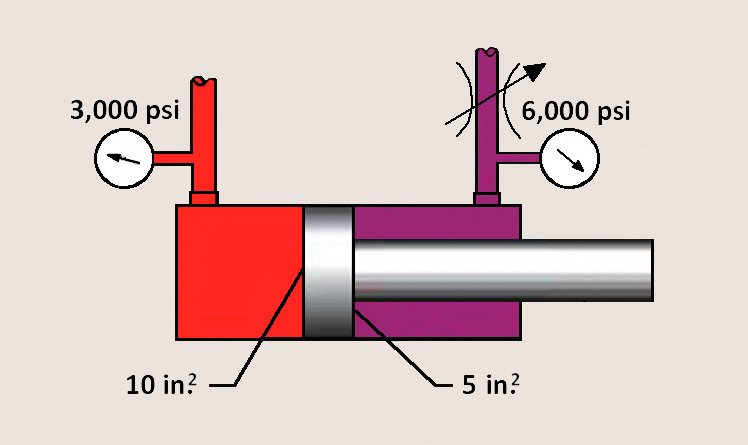

If the cylinder had a 2:1 area ratio between the cap end and rod end of the piston, pressure in the rod end of the cylinder could reach double the pressure in the cap end, Figure 1.

With the rod-end port blocked by the flow meter’s check valve, applying the full 3,000 psi operating pressure to the cap end of the cylinder applied 6,000 psi to the flow meter. Because it was only rated for 3,000 psi, naturally, the flow meter catastrophically failed. Figure 2 shows the failed flow meter.

Training in hydraulics and safety also would have taught the mechanic about different flow meter designs, and how to properly and safely use them. If you are not trained in hydraulics you should not work on hydraulic systems. The result could be serious injury or even death.

If this incident involved you, would you have been so lucky?

This information was provided by Rory McLaren president, Fluid Power Training Institute, Salt Lake City. For more information, call (801) 908-5456, email info@fpti.org, or visit www.fpti.org.

By: Alan Hitchcox

After serving as a vehicle mechanic in the US Army, Alan attended college full time to earn a Bachelor of Science while also working full time for a power transmission and fluid power distributor. He then became a technical editor and wrote or edited hundreds of technical articles for 38 years, with the last 32 on Hydraulics & Pneumatics magazine before becoming semi-retired in 2020.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.