When you install hydraulic cylinder onto a machine, how do you bleed air out of the cylinder?

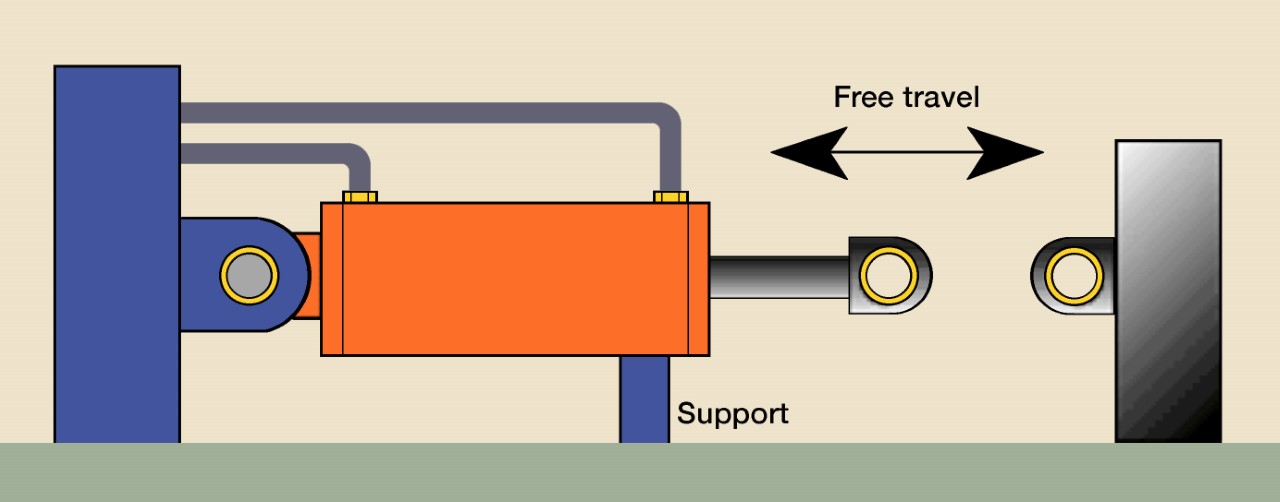

Do you repeatedly extend and retract the cylinder’s piston rod under no load, a technique commonly referred to as free travel? This common practice is unsafe, and you must be aware of and understand the safety problems inherent to this procedure. Here is an example of one such problem.

A maintenance technician was lucky that no one was injured when an accident occurred while he was installing a new hydraulic cylinder onto a production machine. Much of the oil had drained from the hydraulic lines between the cylinder and directional control valve when the technician removed the old cylinder and installed the new one. He figured that by repeatedly extending and retracting the cylinder’s piston rod, the air in the hydraulic lines would eventually work its way into the reservoir.

He installed the clevis pin on the cap end of the cylinder and planned to install the rod-end clevis after purging the air from the hydraulic system. The cylinder’s piston rod was fully retracted and the cylinder contained a negligible amount of oil in it.

After connecting the hoses to the cylinder, the technician started the power-unit with the intent of purging the air out by repeatedly extending and retracting the cylinder’s piston rod. Although the rod did not immediately move when he shifted the directional valve to extend it, the rod began to move after a few seconds. It then accelerated rapidly and continued moving even after he shifted the directional valve back to the neutral position. The rod then blew out of the rod end of the cylinder after shearing the cylinder’s four tie-rod bolts.

An investigation determined that hydraulic oil entering the air-bound transmission lines compressed the downstream air in the lines. When the pressure overcame the initial resistance to move the piston rod, the compressed air expanded, causing the cylinder rod to accelerate at high velocity.

Instead of trying to bleed air from the system by allowing the piston rod to “free-travel,” he should’ve first bled air from the hydraulic system using a hydraulic microbleed valve or other safe method that does not expose an open hydraulic line or port to atmosphere. More specifically, he should’ve followed safe procedures recommended by the manufacturer of the machine.

This information was provided by Rory McLaren president, Fluid Power Training Institute, Salt Lake City. For more information, call (801) 908-5456, email info@fpti.org, or visit www.fpti.org.

By: Alan Hitchcox

After serving as a vehicle mechanic in the US Army, Alan attended college full time to earn a Bachelor of Science while also working full time for a power transmission and fluid power distributor. He then became a technical editor and wrote or edited hundreds of technical articles for 38 years, with the last 32 on Hydraulics & Pneumatics magazine before becoming semi-retired in 2020.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.