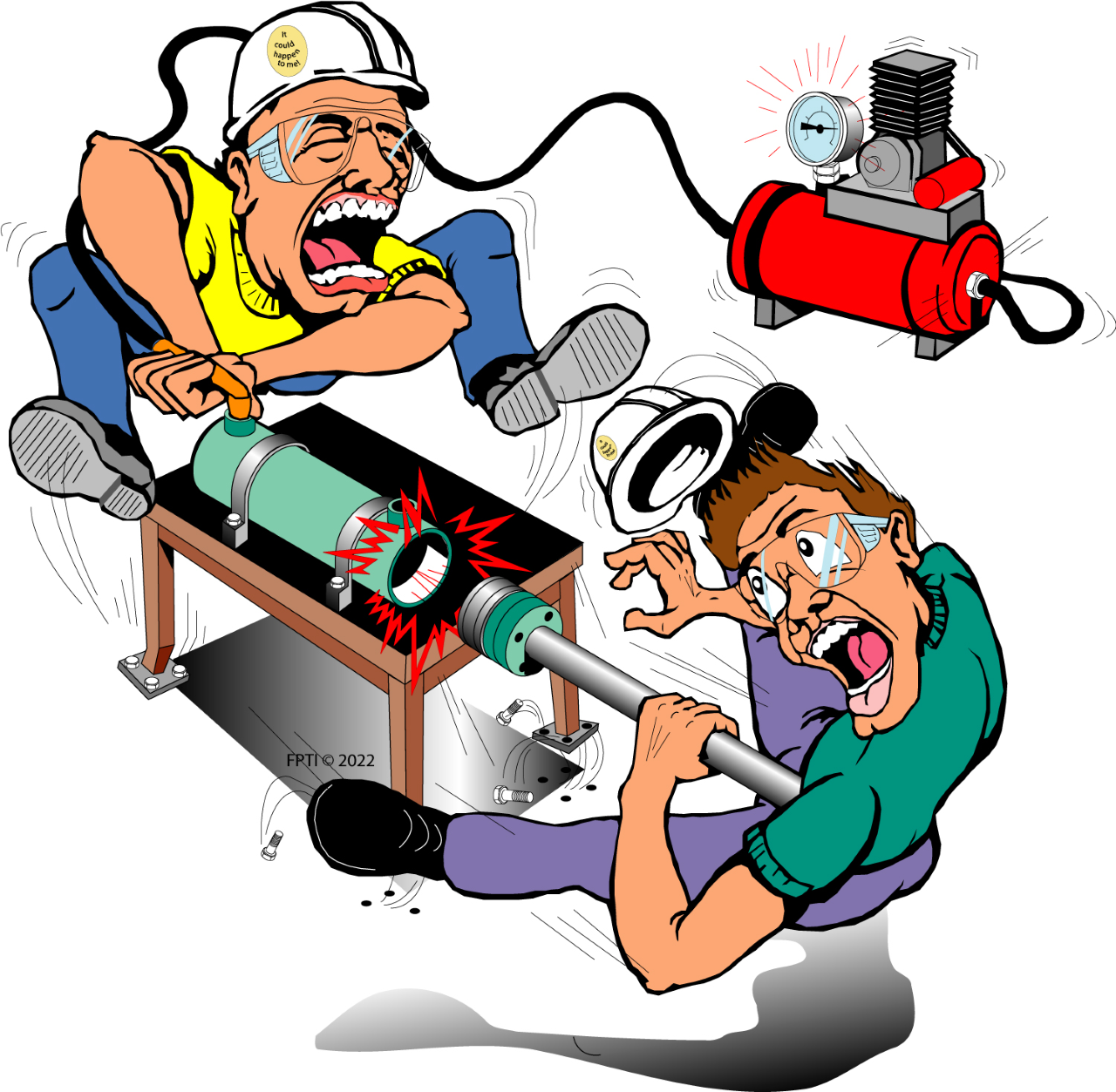

A Routine Procedure Gone Horribly Wrong

One of the most effective ways of learning is learning from your mistakes. What’s even better is learning from someone else’s mistakes. That’s why I go back to Rory McLaren again and again. Rory is an instructor and expert on fluid power safety, and director of the Fluid Power Safety Institute. He has shared dozens of stories that describe situations many of us could find ourselves in.

Here’s one such story about two guys conducting what sounds like routine procedures for cylinder repair. Unfortunately, the consequences were anything but routine.

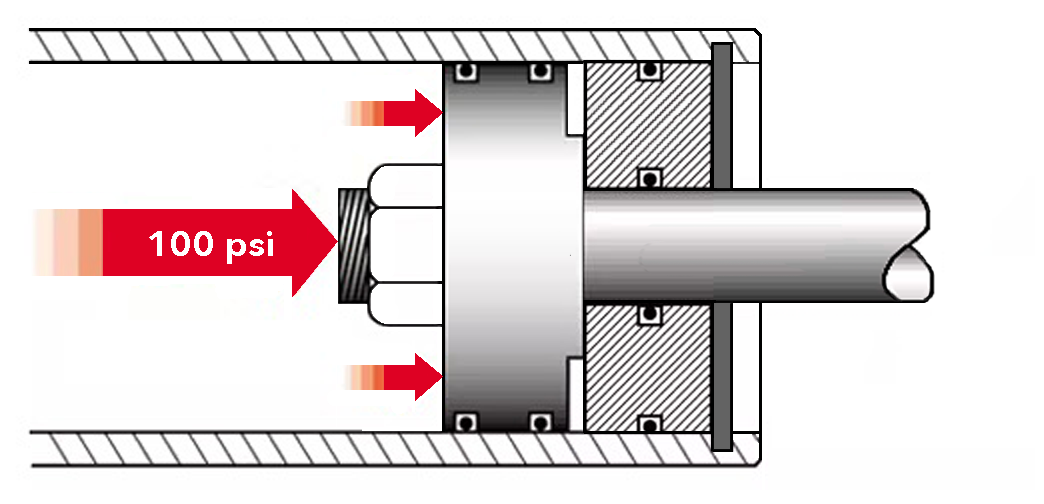

A maintenance supervisor and a mechanic were severely injured as a result of an accident they caused while disassembling a large hydraulic cylinder. The accident occurred when they tried to remove the cylinder’s rod & gland assembly. They secured the cylinder to a workbench and then connected a compressed air hose to the cylinder’s cap-end port. They figured 100 psi of shop air should generate enough force for the piston to push the rod & gland assembly out of the cylinder.

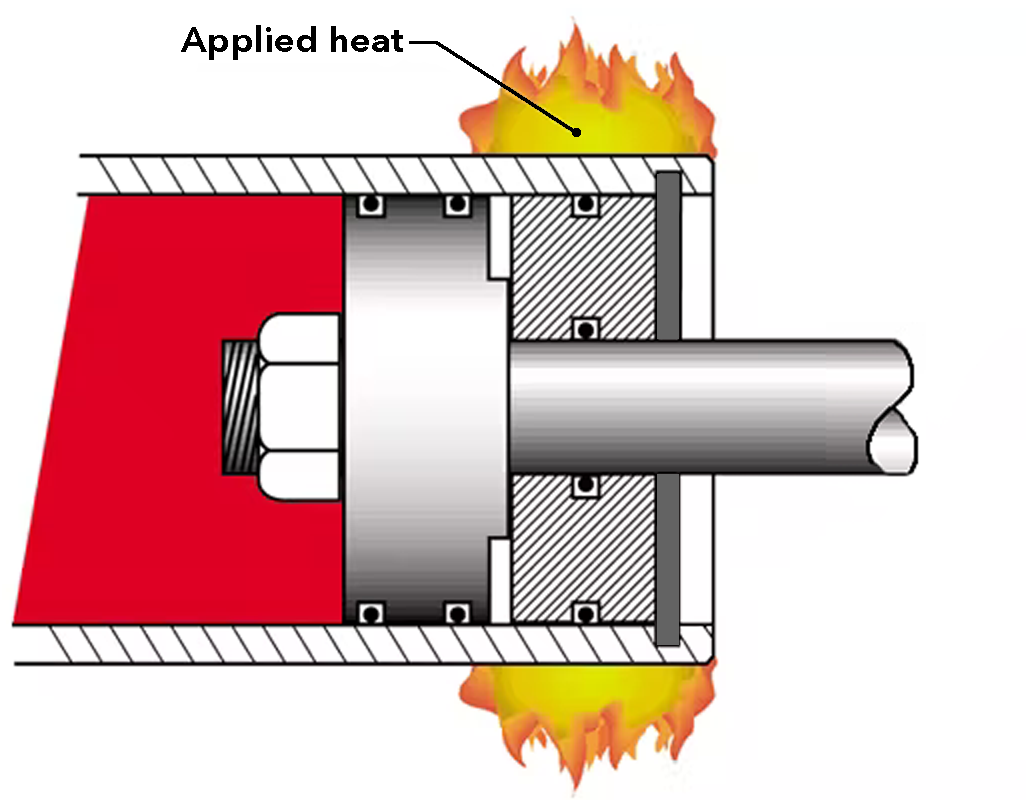

When pressurizing the cylinder didn’t push the rod & gland assembly put, the workers decided to heat the rod end of the cylinder barrel. Their intention was to expand the diameter of the cylinder tube, thereby releasing its grip on the gland. They used an acetylene torch with a rosebud tip to apply heat to the surface of the cylinder tube.

After a few minutes, the rod & gland assembly unexpectedly shot out of the cylinder with a deafening explosion that was heard throughout the complex. Both men were knocked to the ground by the force of the explosion and were both covered in hydraulic oil as it sprayed out of the open end of the cylinder tube and engulfed in flames.

A passerby grabbed a fire extinguisher and doused the flames. The heavy gland had ripped one man’s leg off as air blasted it out of the cylinder. He also suffered extensive burns. The other worker and suffered extensive burns and a broken leg.

Details of What Happened

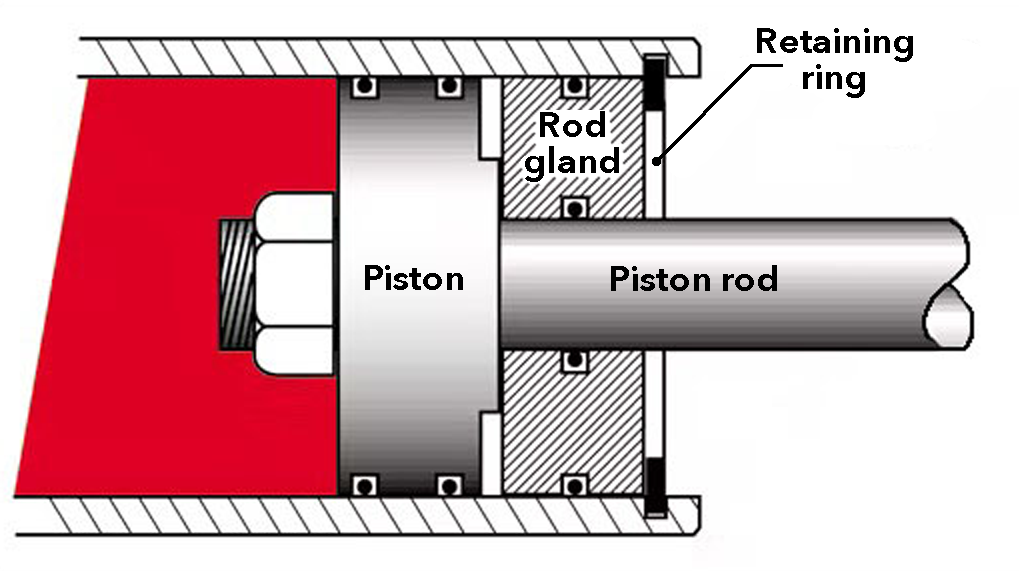

While performing routine service on a large hydraulic cylinder, which included inspecting its internal wear rings, the mechanic noticed signs of external leakage from the rod seals in the gland. The cylinder design was typical of those found in mobile hydraulic applications: a gland assembly recessed inside the rod end of the cylinder tube. The assembly is held in place by a steel retaining ring that fits into a groove machined into the ID of the cylinder tube.

After removing the retaining ring, the mechanic tried in vain to extricate the rod & gland assembly manually. All indications were that it was seized. Next, he attempted to pull the rod & gland assembly out using a cable attached to a forklift truck. The gland assembly still didn’t budge.

They discussed the problem and together they decided to try to push the stubborn gland assembly out using compressed air. They went so far as to calculate the force that 100 psi would generate against the piston area to push the gland outward.

They installed a quick-disconnect coupling to the cylinder’s cap-end port, then connected an air hose from the compressor to the coupling. They monitored an air pressure gauge to ensure they applied a full 100 psi of compressed air. However, the resultant force still did not push the gland assembly out.

After further discussion, the workers decided that the cylinder tube’s grasp on the gland assembly might be released by applying heat to expand the cylinder tube in the vicinity of the gland. Using an acetylene torch with a special tip for heating. The mechanic applied heat to the cylinder tube uniformly by moving the torch tip around the OD of the tube. After three minutes or so, the explosion occurred.

The heat applied to the end of the cylinder barrel did, indeed, expand its diameter enough to release the gland. However, it also heated the air inside the cylinder to increase its pressure well beyond 100 psi. It also heated residual oil in the cylinder. As a result, the air-oil mixture ignited into a fiery inferno when it contacted the torch’s open flame.

A common occurrence?

Unfortunately, the results of an industry-wide survey of heavy-duty mechanics yielded discouraging results —over 90% of the heavy-duty mechanics we spoke to have either used compressed air to remove a rod & gland assembly or know someone who has.

This shows not only that is this a common practice, but also one that is regarded as acceptable. Even companies with the most rigorous safety programs may overlook this critical safety issue.

How this accident could have been prevented

Training. There is no tool that is more effective at reducing or eliminating work-related accidents than training. This accident would not have occurred had the victims received proper training on how to disassemble a hydraulic cylinder — a straightforward procedure for a properly trained person.

Supervisors often assume that mechanics can figure out disassembly and assembly procedures from their own experience. But if mechanics have not learned proper, safe techniques, they’ll just repeat the safe potentially unsafe practices again and again, until a serious accident occurs.

Follow service and repair instructions —Component and machinery manufacturers must provide clear, safety-based, accurate information that is user-friendly. The manufacturer must clearly state if specialized tools are needed for a particular task, and make those tools available. If specialized skills are needed to do the job, they must be stated.

Proper tools — Specialized tools are needed for almost any job like this. A hydraulic technician should have flow meters, pressure gages, temperature gages, and any other special tools required to service and repair hydraulics.

How to safely remove a stubborn rod or gland*

- Wear safety glasses.

- Place the cylinder on a suitable table and secure it in a vertical position.

- Remove the retaining ring or other locking device from the gland assembly and refer to the cylinder manufacturer’s information for guidance.

- Pull the rod until it stops against the cylinder’s gland assembly.

- Place a suitable support under the rod to prevent it from falling, which could cause injuries. The support will also prevent the rod from getting damaged when it comes out.

- Place a suitable vessel under the cylinder to catch the oil when the rod and gland assembly come out.

- Plug the port in the rod end of the cylinder with a suitable plug that has the proper pressure rating.

- Tilt the cap-end of the cylinder upwards slightly and place suitable spacer (about 1 in.) under it.

- Fill the cylinder (through the cap-end port) with hydraulic oil.

- Connect a 300-psi mechanical hand-pump with pressure gauge to the closed-end port.

- Gradually pump the hand pump while observing the pressure gauge. The rod/gland assembly should begin to move. Keep on pumping until the rod/gland is pushed completely out of the cylinder tube.

- If the rod/gland assembly does not move the time the pressure reaches the maximum pressure rating of the cylinder, suspend pumping and release the pressure.

- Call the cylinder manufacturer for guidance.

*This procedure is recommended for occasional cylinder service and repair only. For high-volume cylinder service and repair, we recommend that you consider acquiring a proper cylinder-service repair bench.

Warning: do not continue gland removal using trial-and-error methods.

This information was provided by Rory McLaren president, Fluid Power Training Institute, Salt Lake City. For more information, call (801) 908-5456, email info@fpti.org, or visit www.fpti.org.

By: Alan Hitchcox

After serving as a vehicle mechanic in the US Army, Alan attended college full time to earn a Bachelor of Science while also working full time for a power transmission and fluid power distributor. He then became a technical editor and wrote or edited hundreds of technical articles for 38 years, with the last 32 on Hydraulics & Pneumatics magazine before becoming semi-retired in 2020.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.