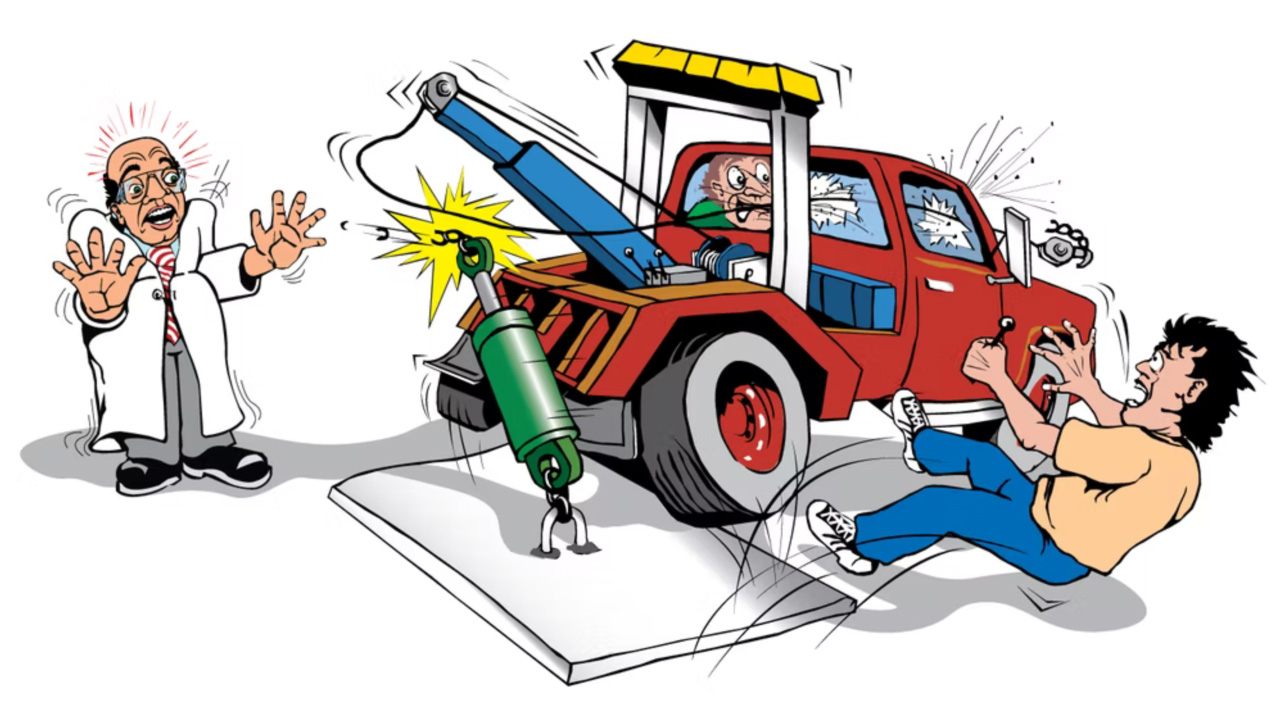

Students at a technical college were going to learn how to disassemble a hydraulic cylinder. In this case, the cylinder was a round, welded design with the rod gland retained on the ID of the cylinder tube. Students removed the gland retaining ring, then laid the cylinder on the floor. They then tried to pull the rod and gland out together. The gland wouldn’t budge, so they needed to figure out how to generate more pulling force.

With the instructor’s help, the students jury-rigged an apparatus they thought would work. They welded an anchor to a large steel plate and attached the cap end of the cylinder to the anchor using a chain. The pulling-force would be generated by a hydraulic winch on a tow truck. A student backed up the truck so its rear wheels were on the plate. The truck’s tires would hold the plate firmly against the concrete workshop floor while its winch would pull on the rod.

The crew then attached the hook on the end of the winch’s cable to a chain, which was fastened to the cylinder’s rod-end clevis. With the setup complete, one student sat in the driver’s seat while another operated the winch’s valves, which were located at the back of the tow truck. The other students and instructor watched intently as their experiment moved from planning to execution. The driver started the truck and kept its brake pedal depressed.

The winch started to rotate slowly when the student activated the winch lever. The winch effortlessly lifted the cylinder into the vertical position, readying it for pulling action. The student in the driver’s seat twisted his torso and wrapped his right arm over the seat so he could observe through the rear window of the truck cab. The instructor gave a “thumbs-up,” so the valve operator activated the lever so the winch would begin pulling. The rear end of the tow-truck inched down, and the tires deflected as the winch torque increased to meet the resistance force of the stubborn rod gland.

A thunderous explosion erupted when the chain connecting the tow-hook to the rod clevis unexpectedly snapped. The action of the vehicle bouncing up, the tires springing back to normal, and the cable losing its tension caused the cable and hook assembly to recoil violently and be propelled toward the truck’s rear window.

The students watched helplessly as the projectile sailed through the vehicle’s rear window and out through the windshield. The student sitting behind the wheel froze as the steel projectile flew through the cab—missing his face by inches. Shards of broken glass became miniature projectiles as they pummeled the inside of the cab. The broken hook assembly came to rest over the end of the tow-truck’s hood. Needless to say, the students and instructor were fortunate to survive without injury.

The lesson in “trial-and-error” was over. However, the lesson wasn’t a complete failure because the students learned how not to disassemble a hydraulic cylinder. Had the procedure been successful in freeing the gland, the students would have probably graduated having mistakenly learned that constructing a makeshift mechanism without knowing the strength of the relative materials is an acceptable way to remove a gland stuck in a cylinder. This is how unsafe maintenance practices perpetuate throughout industry and create accidents waiting to happen!

This attempt failed because rust had accumulated between the gland and cylinder wall, which caused the gland to seize. Cylinder repair is best left to the experts. Handling, assembling, and disassembling cylinders (especially the round, welded type) require specialized fixtures and tools. Because none of these individuals were qualified to repair hydraulic equipment, they should have sent the cylinder to a certified hydraulic repair facility.

Warning: Do not attempt removing a stubborn end-cap gland using trial-and-error methods.

Click here to read the safe way to remove a stubborn end gland and piston rod.

This information was provided by Rory McLaren president, Fluid Power Training Institute, Salt Lake City. For more information, call (801) 908-5456, email info@fpti.org, or visit www.fpti.org.

By: Alan Hitchcox

After serving as a vehicle mechanic in the US Army, Alan attended college full time to earn a Bachelor of Science while also working full time for a power transmission and fluid power distributor. He then became a technical editor and wrote or edited hundreds of technical articles for 38 years, with the last 32 on Hydraulics & Pneumatics magazine before becoming semi-retired in 2020.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.